Strategies for the Physical-Behavioral Healthcare Integration Puzzle

Leveraging value-based care, correctly assessing the technology’s capabilities, and empowering primary care are at the heart of physical and behavioral healthcare integration.

Source: Getty Images

- Physical and behavioral healthcare integration is a key aim for many private payers, but progress has been slow.

Brett Hart, chief behavioral health officer at Centene, has more than 20 years of managed care leadership experience and is also a licensed psychologist with a doctorate in Clinical Psychology. As such, he is very familiar with the healthcare industry’s challenges in addressing behavioral healthcare.

“It's important to really rewind a bit and look at the history of behavioral health as it has existed over the last 30, 40 years—and has even persisted into the last few years. That's a history marked by behavioral health being carved out of most health plans and being disconnected and fragmented,” Hart told Healthcare Strategies.

“Fast forward to the present, payers not only must contend with those historical barriers, but with new challenges as well,” Hart added.

For example, the “false perception that placing behavioral healthcare and physical care providers in the same building or location equates integration.”

“Physical integration does not necessarily translate to actual integration of care,” Hart said.

Challenges like this have resulted in a blaring need for more behavioral healthcare, Marilyn Serafini, director of the Health Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC), which has championed for physical-behavioral healthcare integration.

“We know that in 2019 not even half of people with mental illness actually got treatment, that's a big deal,” Serafini told HealthPayerIntelligence. “The need is enormous, the problems are complex, and it's expensive.”

In order to push forward physical-behavioral healthcare integration, private payers will have to integrate mental health and substance use disorder treatment strategies, accurately assess the role of technology, leverage value-based care, and empower primary care providers.

Brett Hart, chief behavioral health officer at Centene

Source: CenteneStarting with substance use disorder, mental healthcare integration

Before payers can achieve more widespread, lasting integration of behavioral and physical healthcare, they must address the urgent demands of members who suffer from substance use disorders, Hart suggested.

“It's difficult to address the integrated needs of someone with a physical health condition if we haven't pulled together an integrated solution to addressing mental health and substance abuse comorbidities,” Hart said.

Substance abuse is a form of behavioral healthcare that is closely tied to mental health conditions. Approximately one in four individuals who have a serious mental illness also have a substance use disorder, according to a National Institute on Drug Abuse report.

“There have been great improvements in models of care, very robust analytics driven processes, tools for providers and members to utilize access to digital and tele-enabled care,” Hart outlined. “All of these have really served to bridge that gap between mental health and substance abuse integrated needs.”

However, only 18 percent of substance use disorder treatment programs and 9 percent of mental health treatment organizations offer treatment for patients who have been diagnosed both with a substance use disorder and a mental health illness, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The Affordable Care Act and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (or “Parity Act”) have improved patient access to coverage for both mental health treatment and substance use disorder treatment, the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s report noted.

Private payers such as Tufts Health Plan have worked towards better integration of mental health and substance use disorder treatments by partnering with provider organizations that have similar goals and are geographically accessible to members.

“With that being addressed, this really allows us to more fully turn our attention to medical behavioral integration,” said Hart.

Indira Paharia, chief operating officer for behavioral health at Centene

Source: CenteneRecognizing the role of technology

Technology is fundamental to facilitating behavioral healthcare, but payers have to embrace an accurate perspective of its capabilities and role in physical-behavioral healthcare integration.

Digital tools are key to identifying patients that may require a behavioral healthcare intervention.

“By examining utilization patterns, utilizing predictive models, artificial intelligence, these have been wonderful innovations that have really allowed us to more fully and accurately detect individuals with behavioral health conditions,” Hart said.

Payers can then push that data to providers using digital platforms so that providers can be aware of their patients’ behavioral healthcare history and can monitor progress.

“Investments in data analytics and technology will continue to be needed by payers to effectively push data to providers in real time,” Hart stated.

“We have to understand that when a provider is working in the office, they only have brief periods of time they can spend with any given patient. If there are behavioral health needs that a payer may be aware of, it's important that we get that to that physician quickly in real time.”

Real-time data analytics has evolved rapidly in recent years, in part aided by the coronavirus pandemic which, to some extent, nullified the usefulness of historical data.

Beyond real-time data analytics, the healthcare technology sector, in general, has exploded in the last ten to fifteen years. Disruptors and startups in this area are flourishing.

Payers may build partnerships with leaders in this healthcare technology to develop digital solutions for physical and behavioral healthcare that will further integration.

For example, Centene has employed behavioral healthcare platforms and telehealth tools for providers that promote holistic, collaborative care with real-time data, added Indira Paharia, chief operating officer for behavioral health at Centene.

As a part of its integration strategy, the payer announced plans to acquire Magellan Health in January 2021. If the deal is finalized, it would leave Centene with one of the largest behavioral healthcare platforms in the nation, serving 41 million members.

Providers also rely heavily upon telehealth for behavioral healthcare treatment. In 2020, nine out of the top ten diagnoses that were assessed via Centene’s telehealth tool were related to behavioral healthcare.

Telehealth can also address specialized needs, Hart added. For example, telehealth platforms can now support members with eating disorders, substance use disorders, and school-based care.

Not only are telehealth tools able to home in on the specific needs of smaller populations, but these technologies can also broaden access to behavioral healthcare for the general public.

The small behavioral healthcare workforce remains one of the major challenges in behavioral healthcare.

Michael Renzi, DO, president of healthcare delivery at CDPHP

Source: CDPHPMichael Renzi, DO, president of healthcare delivery at Capital District Physicians' Health Plan (CDPHP), saw this issue at work in his own health plan.

“If you have a government product like Medicaid, you're going to have a really tough time finding a behavioral health provider,” Renzi explained to HealthPayerIntelligence.

“At CDPHP, that's unacceptable, but the problem is that we had no network. So we said, ‘It doesn't need to be brick-and-mortar. It can be all digital.’ Psychiatry, behavioral health lends itself extremely well to that.”

But even as the payer built out its technological strategy for expanding access to behavioral healthcare, Renzi knew that digital solutions did not solve the inadequate behavioral healthcare workforce—not just the lack of behavioral healthcare therapists, but also the lack of prescribers.

Therefore, the health plan encouraged partners in geographies with the network capacity to create telehealth “micro-networks” that include both therapists and prescribers. The networks collaborate through an EHR that the health plan can access to easily exchange data and push information to the providers.

"Did the tech solve the problem? No. The network solved the problem, but the technology-enabled the network to be successful,” Renzi stated.

Renzi emphasized that payers need to find the right place for technology amid attempts at integration.

“The same problem that we had prior to when the CD-ROM showed up in my office and I put in my first EMR in 1999 are the same problems we have now: technology is not forcing us to a higher level of quality,” Renzi explained. “It's certainly doing nothing for the cost of care, right? The cost of care is still out of control.”

Technology is not the focus of physical-behavioral healthcare integration, Renzi underscored. The patient experience should be at the heart of this effort.

“We enjoy very high net promoter scores at CDPHP because we've realized that the experience of the member couched in quality is really what the member wants,” Renzi shared. “We went to a very consumer-centric type of approach. Technology needs to be a tool to accomplish the mission. It's not the backbone for mission success. It's about people and process. And the people and process have to be enabled by technology.”

Marilyn Serafini, director of the Health Project at BPC

Source: Bipartisan Policy CenterLeveraging value-based care

Value-based care and value-based payment models can be a vehicle for physical-behavioral healthcare integration, experts agreed.

“As it relates to behavioral health, first of all, the biggest way to improve value-based care for behavioral health is to integrate behavioral health within those value-based systems,” Serafini said.

“Value-based care is really the low-hanging fruit when it comes to integration. While there are other pathways that lead to integration, value-based care is already set up to do it. The incentives are to give the patient the right care, to give the patient cost-effective care.”

This transition is perhaps most evident in the public payer space, where Medicaid and Medicare provide ample opportunity for more sweeping reform.

“The movement toward value-based platforms such as accountable care organizations and different kinds of managed care arrangements—whether that's in Medicaid, Medicare, or in the private sector—is making it easier, but we're really still in the infancy of moving in that direction and seeing what works and what doesn't work,” said Serafini.

“A handful of states have already implemented behavioral health and primary care integration mostly through their Medicaid programs at this point, but it's very instructive and they've had positive results.”

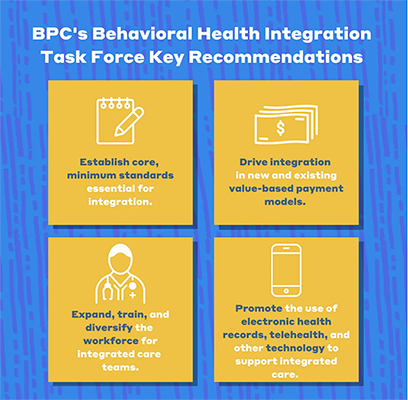

Serafini and her colleagues at BPC recommended that Congress first establish a core set of service elements for what physical-behavioral care integration should look like, including standardized quality measurements.

The healthcare leaders and lawmakers could then use the Medicaid managed care organization, Medicare Advantage plan, and accountable care organization structures to implement integration through value-based payment models.

“We need to see core minimum standards that are essential for integration,” Serafini emphasized. “Currently, there is no standard definition of integrated care across private payer, public payer programs—we’re all over the place. We also need a set of core service and quality standards.”

Although there are no quality standards in place that are specific to physical-behavioral healthcare integration, private payers have found ways to apply other quality measures to this goal.

“We really try to tie things like HEDIS measures into value-based contracting,” said Paharia. “And I think there are a few HEDIS measures that crossover primary care and behavioral health. And that's a nice opportunity to do some sort of pay for performance incentivizing of those different provider types really working together in the best interest of the patient.”

At CDPHP, the payer began to incentivize providers to conduct behavioral healthcare screenings in order to nudge along physical and behavioral healthcare integration.

“We pay the network to pay extra special attention to behavioral health issues, get in there and get these members identified, and try to talk to them about treatment,” Renzi explained. “The most alarming thing is how many patients you weren't ever planning on asking about depression score very badly on a depression screen.”

But, like BPC, Renzi acknowledged that the work would not stop there.

“Now the next pivot is going to be to get the outcome that we need—and that is to get depressed patients feeling better,” Renzi said.

For private payers, transitioning behavioral healthcare services into value-based care agreements will require attentive collaboration with provider partners.

“It’s important that we support our providers in navigating their way through the value-based payment continuum in order to ensure their success,” Hart said.

“Our goal in using value-based arrangements is to reduce the administrative burden on providers and really equip them with the tools designed to create visibility regarding patient progress, regarding gaps that may need to be addressed. We can do this by supporting and incentivizing patient screenings, providing data on patient progress, equipping ease of interaction with primary care. All of these things enable our providers to do what they do best, which is to provide best in class care.”

Source: Bipartisan Policy Center

Empowering primary care services

Payers may choose to focus their physical-behavioral integration efforts on reforming primary care services, making them more cognizant of and prepared for their patients’ behavioral healthcare needs.

Statistically, this is a logical space on which to focus their energies. Eight in ten patients who suffer from a behavioral healthcare condition will present in either a primary care practice or an emergency department, according to the National Council for Mental Wellbeing.

However, primary care providers are not necessarily trained to detect and address behavioral health conditions.

“Look to primary care to handle more of the mild-to-moderate mental health and substance use conditions, and there are a number of ways to do that because they need to be enabled,” Serafini said.

“They don't feel properly educated in behavioral health, they don't feel like they have the right support, time, money, or ability to consult with behavioral health care specialists so that they can feel confident about what they're doing.”

In the public payer space, BPC requested that Congress provide funds for continuing education programs that would help providers across the spectrum including medical translators learn how to work in integrated care settings. These continuing education programs can take place online.

BPC also noted the need for more research on how to effectively train providers to work in integrated care settings.

However, when primary care providers face a patient with a condition that is truly beyond the provider’s capability to address, they should not be expected to offer care.

In such a scenario, empowering primary care services also can mean giving providers the ability to refer patients to behavioral healthcare specialists when the patients’ needs are beyond their capabilities.

But, once again, the inadequate behavioral healthcare workforce presents a major obstacle to connecting patients with needed care.

“There is an enormous shortage of behavioral health providers, and within that we also don't have enough behavioral health providers who are taking insurance,” Serafini said.

“Oftentimes, a patient who is trying to find a behavioral health provider to work with, they will go through that list and they can't find somebody who is taking new patients, or there's a long wait.”

Private payers need to work towards building more robust networks that include behavioral healthcare professionals and connecting these behavioral healthcare professionals with primary care providers.

“That's where things like the collaborative care model have a real opportunity to make a difference,” Paharia said. “But the solutions have to be practical in nature, to take into account how busy primary care providers are and how much of a shortage we're facing with behavioral health providers.”

Expanding that capability may also mean leaning into telehealth more to provide greater access to care.

Implementing these strategies will be key to starting the physical-mental healthcare integration that is so glaringly absent from patient care now. But how payers tackle integration could also set the scene for more holistic, comprehensive care delivery in the future.

In order to shape the future of physical-behavioral healthcare integration, the healthcare industry cannot simply patch holes in the current system. It must also drive change in the upcoming generations of healthcare leaders so that they do not inherit decades’ worth of siloed healthcare practices.