Medicare, Medicaid Home Health Benefits Stabilize Care Costs

Providing Medicare and Medicaid home health benefits may be able to stabilize care costs for older beneficiaries.

Source: Thinkstock

- Providing extended home health benefits for Medicare beneficiaries is likely to stabilize care costs for public payer programs, according to a new analysis from the Commonwealth Fund.

Researchers from the Hilltop Institute and Johns Hopkins University reviewed healthcare costs and outcomes for Maryland’s Medicaid Community First Choice (CFC) Program, which provides supplemental behavioral and long term support services (LTSS) to dual-eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

The team found that per member spending within the CFC Program remained level even as the number of program participants increased and overall expenditures grew.

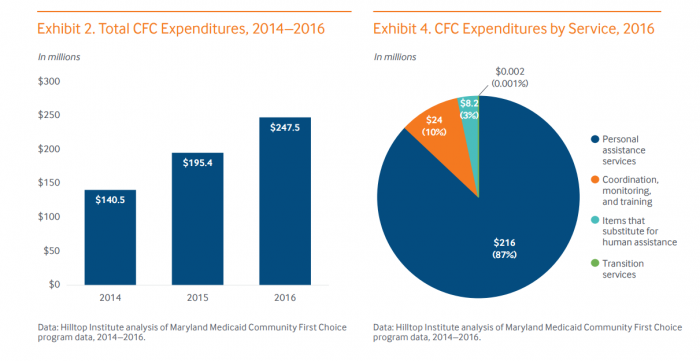

In 2014, the initial CFC cost Maryland a total $140 million, equating to $21,000 per beneficiary for 6,639 participants. In 2015, the number of participants rose to 9,590, but the per member cost dropped slightly to $20,000. By 2016, 11,000 dual-eligible beneficiaries participated in the CFC, costing the state roughly $21,300 for each member.

“The stability of cost per person is reassuring. It suggests that the total cost of providing a HCBS benefit under Medicare or state Medicaid programs can reasonably be estimated by applying the per-member per-year cost to the estimated number of eligible individuals and making reasonable assumptions about trends in take-up rates,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

Source: The Commonwealth Fund

The majority of expenses in the program were for personal assistance services, which cost $216 million, or 87 percent of total program costs, in 2016. Provider monitoring and training was the second largest expense, at $24 million in 2016, followed by other support and transition services.

Medicare beneficiaries (65 and over) required 42 hours per week of personal assistance services in 2014. Beneficiaries required less assistance in each subsequent year. In 2015, Medicare beneficiaries only required 33 hours per week of personal assistance. By 2016, older beneficiaries only needed 29 hours of help per week.

The program also helped reduce personal assistance needs within Medicaid groups.

Medicaid beneficiaries required 44 hours of personal assistance a week in 2014, but only needed 22 hours by 2016.

The team believes a program similar to the CFC program could help improve outcomes for dual-eligible beneficiaries in other states.

“The mean number of hours per member per week declined over the reporting period for both groups, with the decline more pronounced for Medicaid-only participants,” the team added.

The need for informal support services, such as care delivered by family members, friends, or neighbors, also declined as the CFC program developed.

Medicare beneficiaries experienced a 20 percent reduction in informal support services from 2014 to 2016 under the CFC. Medicaid beneficiaries experienced a 22 percent reduction during that same time period.

The team believes that the results of the CFC could help public healthcare payers in other states address the rising costs of care for both Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries.

Mixing both informal and personal care assistance could be a way to provide older Medicaid beneficiaries, and Medicare members, with high quality and cost-effective healthcare.

“Maryland’s experience with the Medicaid Community First Choice benefit design and care model is encouraging,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“The program addresses a number of concerns that arise from adding a ‘Help at Home’ personal care benefit to Medicare. Concerns of substitution for informal care are largely unfounded; rather, a targeted home health benefit (0 hours per week) will likely augment rather than supplant unpaid informal support.”